Part two of my review/commentary on 97 Things Every SRE Should Know

3 - Building Self-Regulating Processes #

tl;dr: Align incentives so that people are intrinsically motivated to follow the process.

The corollary of this is that, however well-intentioned they may be, processes with misaligned incentives will not survive.

I can think of several examples where good ideas didn’t turn into durable processes because the benefits were not seen by the people responsible for doing the work.

If you want people to willingly give up their leisure time to be oncall, make sure their time and contribution is valued appropriately.

If folks are not recognized (and rewarded) for creating and sharing post-incident learning, they will stop doing it (or stop doing it well).

The author (Denise Yu) states:

you can design self-regulating processes if you stop and think about what incentives are in play.

There’s no magic formula provided for getting this right, but it helps to remind folks to consider the question.

4 - Four Engineers of an SRE Seder #

tl;dr: This is an engaging framing of different pillars of SRE by asking 4 questions:

- Selfish engineer: Why is your reliability so poor?

- Junior engineer: It works on my machine. Why isn’t that enough?

- Wise engineer: How can error budgets prevent my next serious incident?

- Unsure engineer: Why is reliability important? Why should we be curious and passionate about it?

To which, I would answer:

- What is the user’s experience of our reliability? How are we measuring that? Which part of the stack are the errors coming from? What quality gates can we add to ensure future releases improve the situation?

- The production environment is necessarily different from a developer’s laptop. There are different security measures in place, different network infrastructure, different scaling requirements, and possibly a completely different runtime environment and architecture / platform. The conditions which make it convenient for you to develop new code are generally very different than the conditions needed to run code safely and repeatably at scale.

- Error budgets are about how much risk you are willing to take with production deployments, or how much leeway you have before needing to make code changes to address the errors. While an error budget may cause you to delay a release/deployment which happens to contain a critical bug, the error budget hasn’t prevented the incident, just time-shifted it to a period of higher baseline availability. It’s a choice whether to include or forgive errors during incidents within the error budget. If you include them, your baseline availability needs to be much higher than your target SLO, but you still have a chance of meeting 28d or 90d targets despite serious incidents.

- This links back to 97things #2: Do we know why we really want reliability?. My answer is that I want to be part of a service which delights and meets a real user need, and does so in a way where the user themself does not have to be concerned about working around outages or glitches in the product. At Google, one of our key reliability targets was “Are we more reliable than your ISP?”. When a service is at least as reliable as a basic utility (water, electricity, etc) then customers can rely on it and factor it into their daily lives without a second thought. Curiosity and passion will keep you open to new ideas and provide the motivation to continuously improve.

5 - The Reliability Stack #

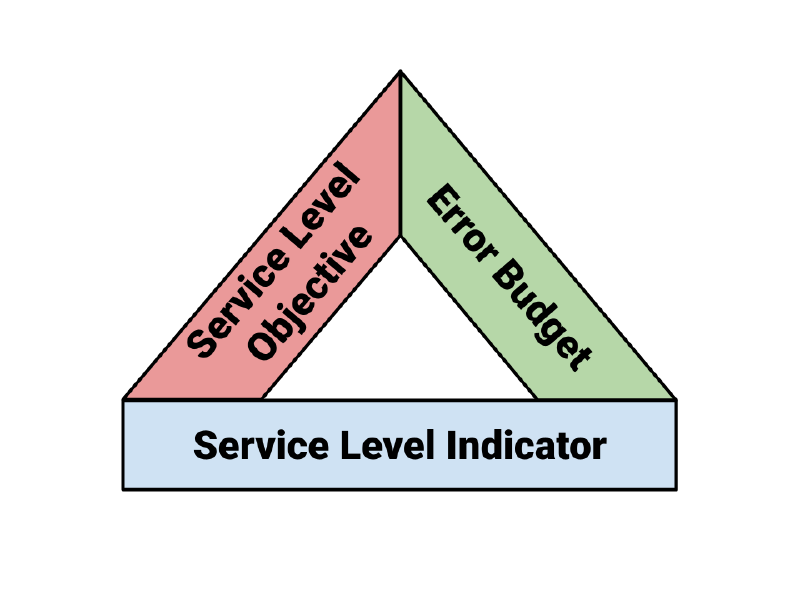

tl;dr: SLIs and SLOs combine to produce Error Budgets

The Art of SLOs workshop is a really effective way to get to grips with SLIs and SLOs, and therefore error budgets (the number of errors you could serve and still meet the SLO).

IMHO calling it “the reliability stack” is unhelpful. Maybe the SLO Triangle would be better? Indicator + Objective + Error Budget